Winning short story about smiles with

Miss Mary Elizabeth Mohler or Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Holter

and my courrageous father who wanted to speak to her, but he needed me ...

"Alice in Nara"

(Originally

written in English)

奈良女子大付属中学校時代に英語を教えていただいたモーラ先生の思い出.

I am looking for Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Holter. Her maiden

name is Miss Mary Elizabeth Mohler.

Any information about her is greatly appreciated! Thank you!

Appeared in Four Seasons, City Press, Kyoto, Japan 1984,1988,...

Fumiko

"Hi,

my name is Alice, Alice in Nara in a wonderland! "

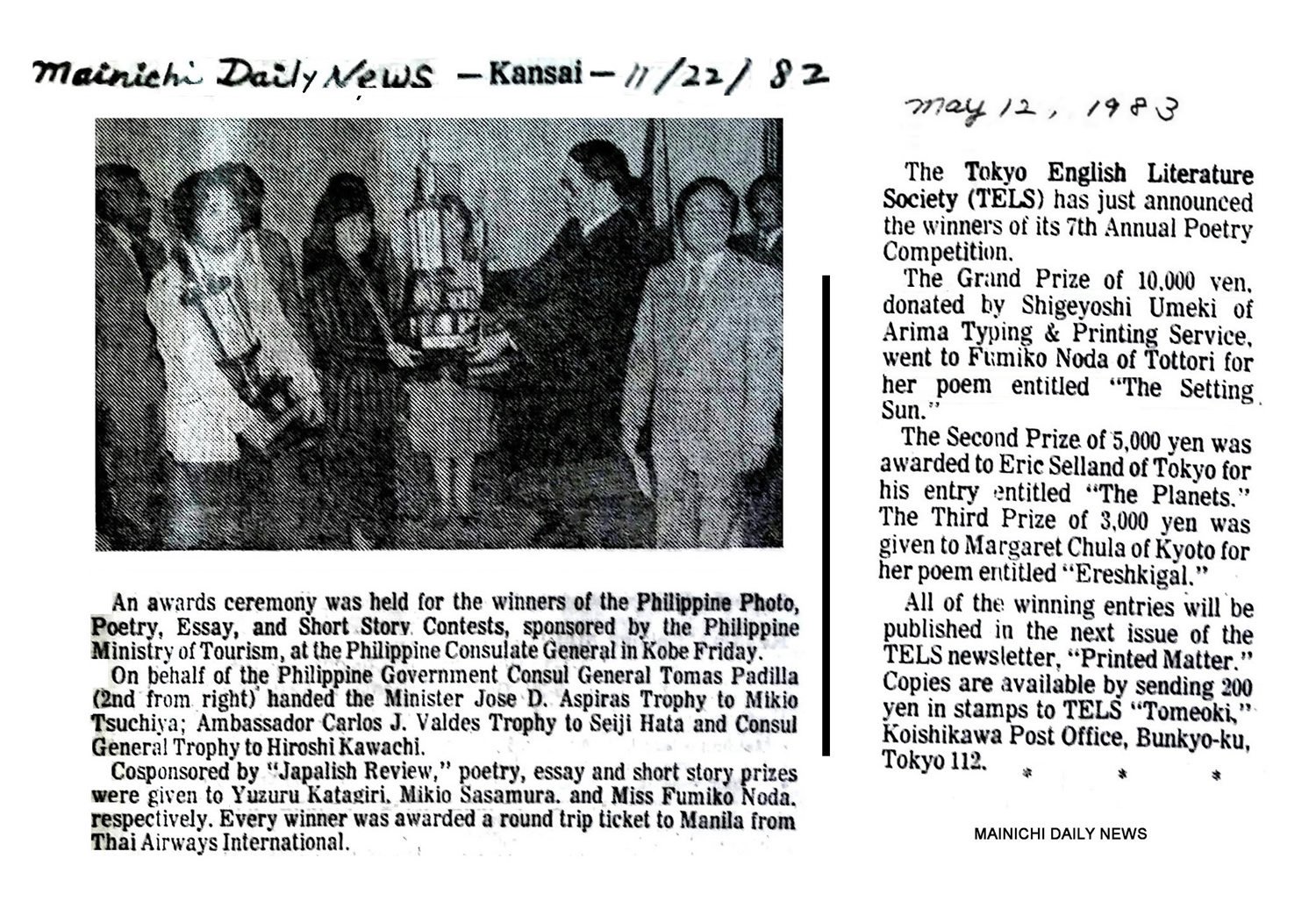

1982,1983の古い記録

Dedicated to my mother

"https://youtu.be/qrT-vrq0-q8

Words: Fumiko Tachibana, New Canadian Review, summer special 1983

Music: Burton V. Foreman, 1994 (About B.V. Foreman: https://www.amazon.com/Way-Lotus-B-V-...

(Sound Source: CD found on 4.2018)

Performed and recorded by the Radio and Symphony Orchestra of Krakow, Poland in

1994.

"Lead Me to Heirinji Temple" by Fumiko (Noda) Tachibana,

Lead Me to Heijinji Temple

I walked alone

through rice fields

and far-reaching sky

a crow perched

on top of a leafless tree

tilting its head

forlorn (ah)

forlorn (ah)

the crow cried

forlorn (ah)

forlorn (ah)

the crow watched

a distorted face

I wish the wind would

carry away my tears

but it's too late

coming this far

to be near to you

but it's too late

🌸

"Alice in Nara"

Originally written in

English

Dedecated to my father

Yoko Nishimura was a student at the

junior high school attached to Nara Women's College.

One day in early April, several

days after the first semester had started, she hurried home as soon as her

classes were over. She walked briskly along the meandering path through Nara

Park, whistling at a couple of tamed deer as they poked their noses into the

fallen blossoms and faint green leaves of the cherry tress that lined the

moss-covered sides of the paths. It was cold, but the sky was bright and there

wasn't a cloud to be seen. She nodded at the deer as she skipped along and

hummed a tune.

Turning into the last path, which

ran through a rice field, she heard a fish-seller's voice shouting.

"Maidoariiiii! Thank you for your patronage. Everyone, come and have a

look at today's fresh fish! Izumi-chan! Maegawa-chan! Nishimura-chan! Irasshai,

irasshai! Come on everyone!" Yoko liked Mr Hirata's wild, playful, and

mischievous shouting and name-calling.

"Mackerel,

?octopus, ?squid and flying fish! Everyone, please come and look!"

His powerful voice penetrated through the hedges and pine trees to the rows of

antiquated wooden houses. And in an instant housewives

in white aprons were making their way out of their houses with metal bowls in

their hands and gathering around Mr Hirata's rusty bicycle which had stopped in

front of Nishimura's garden.

"Konnichiwa! Hello!"

Yoko said, making a quick bow as she passed by the bicycle and the crowd of

middle-aged women whom she knew so well. Hirata chopped up a squid and its

smell began to fill the air. Yoko took a deep, long breath and hoped there

might be squid for supper.

She ran to the garden gate,

opened it, then pulled the sliding front door of the house and went in. The

hallway was full of the aroma of roasting rice-crackers. Yoko took off her

white canvas shoes and made her way to the dining room. Mrs Nishimura, wearing

her white apron, was waiting there for the children to return and preparing

their 3-o'clock snack. She was roasting the crackers over a slow fire in the

round ceramic hibachi.

"Ah, Yoko, hello," Mrs

Nishimura said, her cheeks tinted a little red by the heat of the cooker.

"Mom, I'm hungry," Yoko

said as she put her school bag down on the tatami mat and sat down beside her

mother. She put her hands and chin on the warm rim of the hibachi like a

wistful puppy might do. Mrs Nishimura felt there was something a little odd

about her daughter's behavior.

"There seems to be something

on your mind..." She asked.

"I was very excited

today." Yoko said staring at the ashes in the hibachi.

"Why? What happened?"

Mrs Nishimura turned a cracker over.

"Well, ?Mr

Maeshita, our English teacher, introduced a new teacher to us in class today.

You can't imagine how surprised and excited we were."

"Why?"

"She's a real American! Her

name is Miss Mora."

"Missu Mora?" Mrs

Nishimura repeated what she thought she had heard.

"Yes, Miss Mora. She's going

to teach us English once a week," Yoko said, holding the warm hibachi in

her arms.

"Well, that's very nice. You

are lucky!" Mrs Nishimura said, turning the smoking crackers with a pair

of wooden chopsticks.

"Yes, and Mom, I have an

American name now," Yoko said, and wrote a capital letter "A" in

the ashes of the hibachi with one of the iron tongs.

"American name?" Mrs

Nishimura couldn't make out what Yoko meant.

"Yes, she's going to call us

by English names. Mom, it's exciting to have another name and not a Japanese

one, like Yoko, or Machiko, or Fumiko.

"Alice! Alice! Alice is my

name. I chose it from all the English name-cards she had scattered on the

desks. When she called me Alice for the first time, I was thrilled and felt as

if I were an American. Now I feel as if I were "Alice in Wonderland,"

she said smiling.

Mrs Nishimura smiled too, nodding

at her daughter as she turned the rice crackers over one by one. "Now then

eat up!" she said.

Yoko gazed at the food, but that

was all she did.

"Mom, our class really is a

Wonderland."

She stretched her hand at last to

a cracker that had been roasted and popped it into her mouth.

"Wonderland?" Mrs

Nishimura asked, raising both eyebrows.

"Well, my seat is in front

of the teacher's desk, facing the teacher, you know."

"Then you have to pay

attention..."

"yes,

it has disadvantages. It's sometimes the worst seat for a student to have. I do

have to be alert because teachers often call on me. I hate that. But the one

thing about my seat is that I can watch and secretly examine each teacher's

personal habits. It's so interesting I could write a book about it," said

Yoko, giggling and cracking the cracker.

"Mr Kita, for example, the

math teacher, draws marvelous circles behind him without looking at the

blackboard at all. I like him, but whenever he says something, his right cheek

twitches a little around the mouth. I cup my hands before my eyes whenever it

happens. I can't help giggling, though I try very hard not to."

"You must try to behave

yourself," Mrs Nishimura reproved.

"Mom, believe me, I really

do try to be a good student. I try to learn everything I can from my teachers,

from what they say, and from how they behave," said Yoko.

"This American

teacher," she babbled on, "I've never seen such a gigantic figure in

all my life! She's taller than those GIs who gave me chewing gum at Aburasaka

Station a few years ago. She's a lot taller than any of the other teachers and

boys. She even has to duck when she enters the classroom. Not only that, she

has blue eyes, really deep blue!" said Yoko, who could hardly see the

color of her mother's eyes at all. "And she has an incredibly big nose and

a huge great mouth, so that when she speaks you can see her tongue move back

and forth, twisting and wrenching, right to left, left to right as if it were a

living, creeping creature. I've never seen anybody's tongue move like that. I

mean, no teachers have ever spoken with their mouths so wide open. It seems

barbaric, graceless and indecent. Yet, it's funny!" Yoko said, giggling

with her hands covering her own small thin-lipped mouth. She began to imitate

the way her new English teacher laughed.

"Ha! ha! ha!"

"Ha! ha! ha!" Yoko

continued laughing.

"Don't laugh like that,

Yoko! It's ugly. It's not a thing a young girl should do," Mrs Nishimura

said, raising one eyebrow.

"I've never felt so good,

laughing out loud like this. Why don't you try it? You'll feel good," Yoko

insisted; but her mother pretended not to be interested at all and said,

"Yoko!"

"No, please call me

Alice."

"Well, Ahrisu then."

"No, no. Alice," Yoko

said, moving her tongue upward, licking her upper lip, the way she remembered

she had been taught in Miss Mora's class.

"Al-lice?"

"Just one more time."

"Al-l-lice?"

"Yes, that's much

better!"

They laughed together, and the

sound of crackers being crushed and the loud laughter mingled together and

echoed around the hibachi in the dining room.

The slanted shadows of the wooden

frames of the windows, together with those of the two figures, projected

themselves onto the stiff white paper doors.

![]()

Mr Nishimura taught Japanese

classics at a local college and was very popular among students for both his friendliness

and strictness, his generosity and severity. At home he was both popular and

unpopular with his family because of his femininity as well as his masculinity,

his cowardice as well as his bravery. In fact he was a

strange mixture of two extremes. He often quickly erupted in anger but then it

just as quickly subsided. So before supper there was

usually a panic.

"Papa will be back in a

minute. Yoko, Taiji, Harukuni!" Mrs Nishimura's hysterical howl echoed

from the kitchen to the dining room as the children hurriedly turned off the TV

and began putting things in order and getting rid of the rubbish.

One evening the children had

failed to tidy up the room in time. No sooner had they heard their father's

feet shuffling on the tatami in the next room, when the shoji were pulled open

and lightning flashed.

"What a mess! What a filthy

mess!" Mr Nishimura roared like a tiger.

"Turn off that TV!" (terebi wo keshinasai!)

Yoko hated her father when he was

angry and felt hurt, though she knew that she and the other two were to blame.

Yet the next moment the three children raised their heads, trembling with fear

and terror, and their father was smiling at them as if nothing had happened. He

was sitting cross-legged at the table, calmly reading the evening paper and

sipping green tea.

During supper, sometimes after

this incident, Mr Nishimura, after closely eyeing Yoko for a while, began to

talk to her.

"How is Miss Mora doing,

Ahrisu?"

Yoko was astonished that he had

called her Alice and felt pleased that he seemed interested in what was

happening in her life.

"Did you hear about that

from Mom?" she asked.

"Yes, I know everything that

goes on in this house," he said confidently. Yoko thought to herself how

little he actually knew. He seemed completely unaware that she had started to

menstruate, for example, and she did not know what to say when he urged her to

take a bath on those days. She had been wondering why a man of a romantic,

aesthetic turn of mind could be so insensitive and indifferent to a girl

undergoing the trials of puberty.

"You seem to be interested

in English, don't you, Yoko?" he asked.

"Well, yes, that's true, but

that's partly because I a'm interested in Miss Mora, my American teacher."

I liked English too when I was

young, and yet I didn't like Americans."

"Why not?" Yoko looked

him straight in the eyes.

"Because during the World

War II they bombed our house in Chiba to the ground. God damn them!" he

said, clenching his fists. But the soon calmed down and said, "Still, all

the same, I like English as a language."

"Really?" Yoko asked.

She could not believe that he actually did like English. She remembered his

horrible pronunciation when he read to her from an English textbook a year ago:

"pusshy catto, pussy catto, where habu you been?"

"I know more English words

than you do," he said, pleased with himself.

"But I'm sure I can make

myself understood better than you, Dad,"

Yoko said with her had a little

on one side and not looking at her father.

"NO. I'd beat you any day!

I've got a larger vocabulary," he said triumphantly.

"Well, anyway, Yoko, since

we are both fond of English, what would you say to going over to Miss Mora's

next Sunday?" he suggested.

"Yes, that's a good idea!

Let's just hope the weather is fine," Yoko said, watching the iron

sukiyaki pan that her mother had set on the clay, charcoal stove in the center

hole of the round short-legged table.

"I hope so too, Yoko,"

he agreed, adding some sugar and soy sauce to the well-done, thinly-sliced beef

on the hot pan. White smoke, a hissing sound and the delicious smell of the

meat filled the room

......................................

The sun was already high. The

loud voice of an udon noodle peddler was calling from nowhere. "Udon no

tamma, osoba no tamma, oage-san ni tempura! Udon no tamma, osoba no

tamma..." Yoko heard the voice far away in the distance, in her dream.

Then she was suddently awakened by a faint vibration. She rubbed her eyes and

sat straight up on the futon. "What is it?" she wondered. "I

must be excited," She jumped out of bed, climbed to the window sill nd

jumped into the garden in her bare feet.

"Ouch! Oh, my God,

ouch!" She had landed on a broken piece of porcelain. Blood began to

tickle from one of her toes. "Ouch! Help! Help! "

?She ran into the house through the front door and came across her

mother making tea for her father. Her mother frowned at her.

"Calm down," she

snapped. "It's all right, Yoko. Why don't you be more careful? You ought

to remember the old proverb, 'Look before you leap!'"

Later that day, after a simple

lunch, father and daughter went out together. They said little to each other.

Yoko, in her dark blue school uniform, followed her father a few steps behind.

He wore a dark spring coat and carried a little parcel wrapped in a purple

furoshiki clotth in his arm and a camera slung from his shoulder. They walked

in silence through the rain of falling cherry blossoms in the park, through the

huge wooden gates of Todai Temple, by an ancient pond around which a few deer

were taking a walk and on into the dark, thick, moist forest of cedar and pine

until they reached an old wooden house.

Mr Nishimura stopped in front of

the door. It creaked as he slid it open.

"Gomenkudasai!Excuse

me! Gomenkudasai!" His sharp, loud voice echoed in the deep, dark wooden

hallway.

"Tadaima, I'm coming."

A middle aged woman in kimono, with straight hair in a

bun, was hurrying down the hallway.

"Ah, Nishimura-san!Miss Mora is waiting for you," she said smiling at

him. 'Is this your daughter who wants to talk with Miss Mora?"

"Yes, that's right. Yoko,

say hello," Mr Nishimura urged.

"Hello," Yoko said. She

did not know who this woman was, though she knew from the way they spoke that

the woman must be some kind of an acquaintance. A moment later the woman called

in a loud but clear, thin voice, looking up the steps, "Mora-sensei!

Mora-sensei!"

Yoko waited, feeling isolated

beside her father. She did not know what she was doing here and felt like just

running off home on her own. But just then one of the fusuma glided open, and

at the top of the steps a huge, towering figure appeared.

"Oh, hello, Nishimura-san,

please come in!" she said, beckoning with her hand.

Mr Nishimura urged Yoko to take

off her shoes, and they made their way upstairs. Bowing, the two of them

stepped in. Yoko did not know what to do or say and just waited to see what her

father would do. At the same time she was taking in

the room around her.

There was a large, wooden,

short-legged ebony table, in the tokonoma alcove a bunch of colorful tulips

were arranged in a blue vase. The drab fusuma, yellowish tatami, black table,

lackluster gray walls combined with the familiar rustling sound of the pine

trees which were to be seen through the window. Sitting on the zabuton cushion,

Yoko enjoyed the strange contrast between this large human figure and the

diminutive Japaneseness of the things that surrounded her.

She turned to her father . He was still bowing his head, sitting straight on

the tatami beside the cushion which Miss Mora had put out for him. He was

trying very hard to say something to her, repeating "ahsukueiku,

ahsukueiku, ahsukueiku...."

In spite of his desperate

efforts, Miss Mora could not make out what he was trying to say. Yoko could see

the cold beads of sweat on her father's forehead and turned away to a gray wall

where she noticed a number of pictures of various people that had been pinned

up. There was a smiling middle-aged couple, the man's hand on the woman's

shoulder. A smiling young man. ?Smiling girls. Yoko

wondered how Americans always managed to smile when they had their pictures

taken. She had never seen Japanese couples so close together, or men's arms on

women's shoulders in photographs before. She could hardly imagine her father

and mother touching each other. She could not see why those people in the

pictures were all smiling or what they were smiling about.

"oh,

I see! you mean earthquake!" Miss Mora said at last. Yoko's father was

scratching his head. Then the two of them burst out laughing. Yoko, wondering

what was so funny, laughed politely. She prayed that her father would stop. She

wondered how he could carry on the conversation in that horrible Enlgish of his

and began to feel restless again.

"Jis izu purezento," he

said, giving a little box to her.

"Oh, that's very kind of y

ou!" Miss Mora said, very pleased, and then she abruptly began to tear at

the wrapping paper instead of carefully unfolding it. The thought that

Americans opened a present in this way somehow disappointed Yoko. Having opened

the box Miss Mora exclaimed, "Oh, what a nice present! It looks so

delicious. Thank you very much, Nishimura-san."

"Why don't you try some

yourself?" she said, picking up one of the colorful, sweet jelly-beans

between her big thumb and finger without using the toothpicks in the box.

"Yes, yes, thank you,"

Mr. Nishimura said, just nodding his head.

"How about you,

Yoko-san?" she said smiling at her.

The two adults began chatting

again. But Yoko had no idea what they were talking about.

miss Mora urged Mr Nishimura to

have some more. He repeatedly bowed his head, and then, without looking at Yoko

picked up a piece with his thumb and index finger as Miss Mora had done. Yoko

dutifully followed her father's example.

A long silence fell until Yoko

broke in and asked, "Do you like omochi cake?" She looked Miss Mora

in the eye.

What mysterious eyes! They are

not blue, they are a mysterious mixture of green, gray, gold, silver...

"They're beautiful!" she thought . Yoko

wondered if her English had been understood, but Miss Mora, still munching

away, replied, "Oh, yes, I do. I like it very much How about you?"

"Yes," Yoko answered,

in a very faint voice but now with a renewed pride and confidence, "I

didn't have to repeat what I shad said! That's more than my father can do!

Game, set and match to Yoko!" she thought, as her father continued to

repeat what he was trying to say.

oN their way home the two of them

walked side by side in high spirits. Mr Nishimura did not believe that he had

lost because he had been able to continue the conversation. Yoko believed she

had won the contest. But neither of them spoke about

it

From Four Seaosns:

Page 55

Q

1 Mr and Mrs do not need periods after them. Is this an American or British

English?

2. What is Nara Park famous for?

3. What is "squid" in Japanese?

4. How would you describe a hibachi to a foreigner?

5. What is the reason for Yoko's excitement?

Page 56

6. Do you think it's a good idea for teachers to give their students English

names and use them during class? Say why or why not.

7. "Mom, our class really is a Wonderland." what does Yoko mean?

8. Were any of your high school teachers eccentric? If

so, I n what way?

9. Why do you suppose that Yoko enjoyed laughing at the top of her voice?

Page ?57

10. What is the average height of a young Japanese man or woman nowadays?

11. How dould you describe Mr. Nishimura?

12. Why was Yoko so surprised when Mr. Nishimura enquired about her American

teacher?

13. Why couldn't Yoko believe that her father really liked English?

14. How large of a vocabulary does one need in order to communicate effectively

in English?

Page 58

15. When did the Great Kanto earthquake occur?

16 What is a furoshiki?

17. Explain the differences between an "acquaintance" and a

"friend".

18. How are Americans and Japanese different when posing for a photograph?

19. What did Yoko think of Miss Mora's eyes?

Page 59

20. Mr. Nishimura did not seem at all worried about his poor accent. What do

you think of his attitude?

21. What is your impression of Miss Mora?

22. Why do you suppose that neither Yoko nor her father spoke about the outcome

of the contest?

23. Who do you think won the contest?? And why?

24.

How would you re-title this story?

This story received first place at the writing contest

for non-native speakers of English, and got 副賞フィリピン旅行

round trip tickets to Manila,

awarded by Phillipine Ministry of Tourism and Japalish Review, Kyoto.

この授賞式には世界の京都精華大学教授片桐ユズル先生が詩のセクションで受賞されていました。

ジョンペレイラさんが主催するジャパリッシュレビューに掲載されたものから選ばれています。

当時1982年のころ。現在の雑誌の様子はどうでしょう。

Dedicate this story to my father 1989, my mother1980 and two big brothers

Taiji 200. 1.12

and Harukuni. この物語を父と母、2人の兄に捧げます。

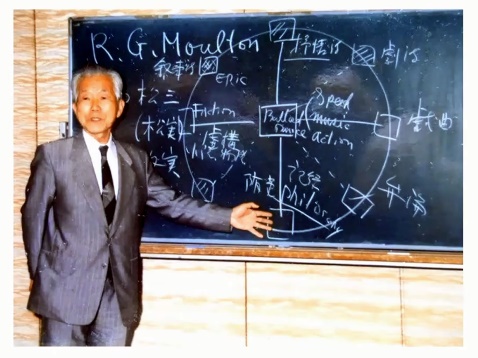

Kenji Tachibana (February 8 1998)橘健二

大鏡 old version Amazon / newer_Amazon

This page is under construction.

工事中のページ

Kenji Tachibana

橘健二

大鏡

大鏡 栄花物語(日本の古典をよむ 11)原文編: (小学館) https://tinyurl.com/y94cm932

1998没、筑波大学名誉教授

父は山岸徳平先生を愛し、鈴木先生(東京ー>秋田大学ー>東京)とも親しかった。

奈良付属時代には中村章太郎先生、中西昇先生、井田康子先生(国文)などと交流があった。この部屋は父が秋田大学退職後岐阜女子大に移る前の二年ほど勤務した東京女子体育大学で私が一度訪問したことがある研究室だと思う。父は引っ越しが嫌いじゃない。

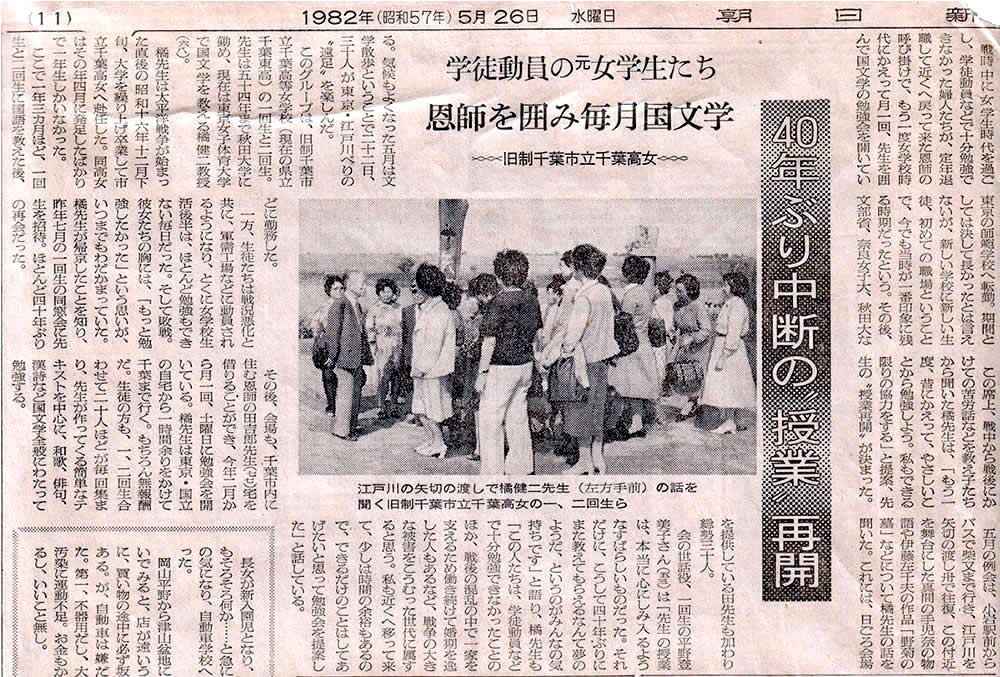

さて若かりし頃高等師範卒業直後に一年か二年、千葉県の女子高に勤務。その後、文部省勤務。千葉の家が焼かれ終戦。千葉の家がやかれていなければ私の運命は違っていたと思う。まだ生まれていなかったころ。(終戦の年に卒業した生徒たちが、授業を満足にうけられなかったので、当時の国語の橘「先生」が千葉の女子生宅まで出向き授業を続行しているという新聞記事が出た。)(新聞記事を発見。下に添付します。)奈良(奈良女子大付属・奈良女子大)市在住(薬師寺、三条添川町)15年、

秋田大学定年退職後、東京(東京女子体育大)都国立市在住。最後は岐阜女子大文学部長にて退官。三重の鈴鹿市の家より勤務。東京半分三重半分という生活でした。 父の父橘ひろしという名前でしたが大阪相田銀行の支店長をして羽振りがよかったらしいです。ただ大正時代の不況のため銀行は倒産。その後、橘黄金鈴たちばなのおうごんれいという文芸ネームで中部地方の新聞の文芸欄の編集長をしていたとか。父から聞いた話。元大阪相田銀行の支店長でしたが大正時代の不況で倒産したらしいです。新しい俳句の運動を始めた人だと、父から聞いた。私が生まれるずっと前のことらしい。知らないことが多く、好奇心が募るばかり。そういう時に話せる親も兄もいない。

この物語はフィクションですが実際の体験が元になっています。私のためだと言いながら父はうきうきしていましたからモーラ先生とお話したかったのは父だったでしょう。でも英語好きにしてやりたいという父の目論みは大成功でした。

Ryoko 亮子

Ryoko Tachibana (July 22 1980) 橘亮子

次兄 Taiji太二

Taiji Tachibana (January 12 2001)橘太二

橘太二おじさんによく抱かれた幸雄。白子の実家にて。ゆきちゃああん、と

かわいがってもらった。一橋大学法学部及び経済学部卒。国立から鎌倉へ

通って塾の講師をしながら司法試験合格をめざしていた。芭蕉を愛す本当に

心やさしかった兄。父のことありがとう。

作品はいろいろと散らばっておりまとめる気力がないのでまた書き

始めるしかないですね。

2002年秋記。 Fumiko

一家が千葉で焼け出されて父は先輩のいる奈良の女子大/付属へ。生後数か月の私。このころ

の私の写真はこの一枚のみです。そんな戦後の時期でした。母は身よりもなく

生きて子供を育てるのに食うや食わずの時代だったでしょう。

at Wakakusa Mountain

橘亮子 (mother)

橘太二 (left) 私 (center) 治国 (right)

朝日新聞 Asahi Newspaper 母の死後の話です

:

長兄治国

10 31 2023 北大日本陸水学会北海道支部会 第 2 代会長 橘治國先生のご逝去を悼む